The grateful foreigner

Esteban Montilla | 23 noviembre, 2024

Being a foreigner

A foreign person is an individual whose native or ethnic origin differs from the nation where they now live. Foreign people often have a different way of speaking or language from the host country, hold views about the world that may differ from the homeland where they currently reside, and embrace dissimilar cultural customs. Sometimes, foreign nationals do not enjoy the same rights as nationals or natives of that state. In addition, there may be circumstances in which the foreigner suffers rejection attacks, hateful behavior, or xenophobic treatment from the natives of the host country.

Foreigners tend to work on the acculturation process to adapt to the new nation and thus minimize discriminatory attitudes and behaviors. In this cultural development, they adopt principles, customs, and procedures that improve their existence and lessen hostile attacks. This is done without abandoning the values and moral compass they bring from their nation and people of origin. Generally, outsiders educate themselves in the new culture, contribute to the economic well-being of the host country, and financially assist the relatives they left behind. It should be noted that, compared to nationals, immigrants are much less likely to commit crimes (NIJ, 2024).

Human beings leave their native country for various reasons, including human curiosity, the search for opportunities for cultural development, improved economic conditions, access to specialized health services, and the desire to live in a politically secure nation. These migratory movements also occur as a result of forced displacement, political persecution, and sometimes for reasons unrelated to the individual, as in the case of children.

The writers of the Torah emphasize the importance of treating foreign people well. “Do not make the stranger who lives among you suffer. Treat them as one of your own; love him, for they are like you” (Leviticus 19:33-34). The Deuteronomistic author refers to God’s special care for strangers. “He pleads the cause of the fatherless and the widow and shows his love for the stranger by providing him with food and clothing” (Deuteronomy 10:18).

The danger of harmful prejudices

In the Christian Bible, there is an account that illustrates how some prejudices held against foreigners are usually the product of evil imagination, malicious speculation, and cruel ignorance.

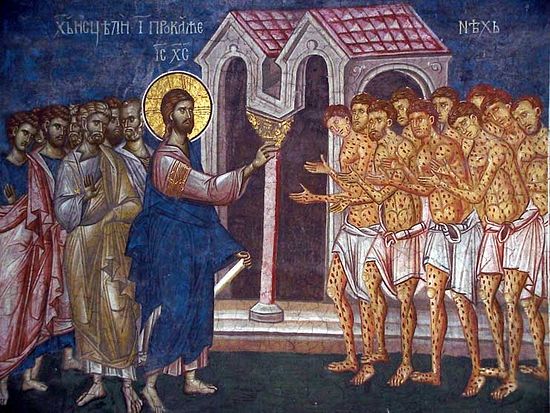

“On his way to Jerusalem, Jesus passed through the regions of Samaria and Galilee. And he came to a village, where ten men sick with leprosy met him, and they stayed far away from him, crying out: -Jesus, Master, have mercy on us. When Jesus saw them, he told them, Go and show yourselves to the priests. And as they went, they were cleansed of their infirmity. One of them came back when he was cleansed, praising God loudly. Kneeling before Jesus, he bowed himself to the ground and thanked him. This man was from Samaria. Jesus said, “Were not ten who were cleansed from their sickness? Where are the other nine? Has only this foreigner returned to praise God? And he said to the man, “Arise and go your way; by your faith, you have been healed” (Luke 17:11-19).

The author of this story uses a cognitive strategy to dismantle a dangerous and absurd belief such as ethnocentrism, i.e., thinking that one cultural group is better and superior to another. Judaism is an ethnicity and also a Canaanite religion that was formulated between 700-300 B.C. (Finkelstein and Silberman, 2001; Finkelstein and Amihai Mazar, 2007; Adler, 2024). In the elaboration of national identity, the writers of the first five books of the Hebrew Bible suggested that there was a Patriarch named Jacob, who had twelve sons, but that one of them, Judah, was the privileged one, the best and superior to the others (Genesis 49:8-12).

According to these texts, Judah and his descendants settled in the southern region of Canaan (Jerusalem, Hebron). The writers propose that this group of human beings from the south (Judah, Jews) were superior, refined, kind, righteous, educated, and preferred by God. But, on the other hand, those who lived in the center (Samaria) and the north (Galilee) were people they considered uneducated, cruel, ungrateful, idolatrous, unjust, and the worst of humanity. The author of Luke’s Gospel submits that this perception is entirely wrong.

To demolish this erroneous belief, he first uses the account of the Good Samaritan (Luke 10:25-37), where he presents the Samaritan acting in a compassionate and hospitable manner. In Luke 17 of this account, he places the Samaritan as the person who shows gratitude. Another essential aspect to highlight is that the Jews considered Jesus of Nazareth to be a foreigner and a Samaritan. “The Jews (citizens of Judah) said to him (Jesus of Nazareth) then, -We are right when we say that you are a Samaritan and that you have a demon” (John 8:48, DHH).

The grateful foreigner

In Luke’s account, ten people were healed of leprosy. At that time, this disease referred to any skin disease that changed the color or shape or caused epidermal wounds. Today, leprosy is considered Hansen’s disease, caused by the bacteria Mycobacterium leprae, causing skin lesions and nerve damage. Individuals who were confirmed to have this disease had to be excluded from the community and remain isolated until they were healed and declared clean by a priest. The shame was such that, in addition to living outside the group, they had to wear torn clothes, not comb their hair, and cover their mouths before crying out: “I am unclean, I am unclean” (Leviticus 13:9-17; 14:1-32).

This is how the protagonist of Luke 17, besides being a Samaritan or foreigner, was a man diagnosed with leprosy. Intersectionality, or the crossing of two or more cultural identities on the margins, can make a person more vulnerable to discriminatory acts and victims of hate crimes. Upon being healed, this foreigner returns to thank the one who encouraged him to believe in himself and work on his restoration. This man from Samaria “with a loud voice” (Luke 17:15-16) thanked God and showed respect to Jesus of Nazareth.

Jesus said, “Were there not ten who were cleansed of their infirmity? Where are the other nine? Has only this stranger returned to praise God?” (Luke 17:17-18, DHH). So, the one who was expected the least — the foreigner — and was presented as a person of little value ended up being the one who acted in a respectful, grateful, and dignified way. Jesus reminds the man from Samaria that his willingness and decision to follow the recommendation had much to do with his healing. The healing came from the collaborative work of Jesus of Nazareth, who encouraged him to believe in God and the Samaritan. “And he said to the man, ‘Arise and go your way; by your faith, you have been healed’” (Luke 17:19, DHH).